Why distinguishing generations makes no sense

Does Generation Z not want to work? Does it have different work related attitudes? A few years ago, I was asked these questions about Generation Y (supposedly born between the early 1980s and 1999). Now I get such questions from journalists about Generation Z (supposedly born since the year 2000). The immediate cause is typically that yet another TikTok video, management guru, entertainer, activist or Twitter user rumored, almost always without data to back it up, that such and such generation behaves in this or that way.

Such purported generational differences are seemingly supported by the likes of Jean Twenge. However, the way that generations are described are all but clear. For example, Gen Y on the one side is said to subordinate everything to the goal of “getting ahead in their job and career.” At the same time, the same authors write about the same generation that “work and family are far more important to them than a steep career path” (Hurrelmann and Albrecht 2014: 33, 42). Many statements about Generations Z are similarly contradictory; for example if it said that Generation Y has “needs for security, orientation and a sense of belonging [which] stand flexibly alongside performance orientation and ambition as well as the desire for variety, individual development and enjoyment of life” (Klaffke 2014: 73). Such statements are like horoscopes. They claim something and at the same time its opposite. That way, you can always identify with some part of the statement.

But what should we observe, if indeed generations do exist? Simply put, the hypothesis of generations postulates that individiduals are different because of when they were born, regardless of their age and regardless of when you ask them. However, if these latter two effects, known as “age effects” and “period effects”, are taken into account, then there are hardly any “generation effects” left. So you can explain people’s attitudes by their age and you can explain people’s attitudes by when they were interviewed. But you can hardly explain people’s attitudes by their year of birth. And in this respect, there are, measurably, no generations. I can say this because I came to this subject wanting to find out the opposite. A literary agency offered me the prospect of a lucrative book contract if only I could show that Generation Y “is different.” But I just couldn’t find anything.

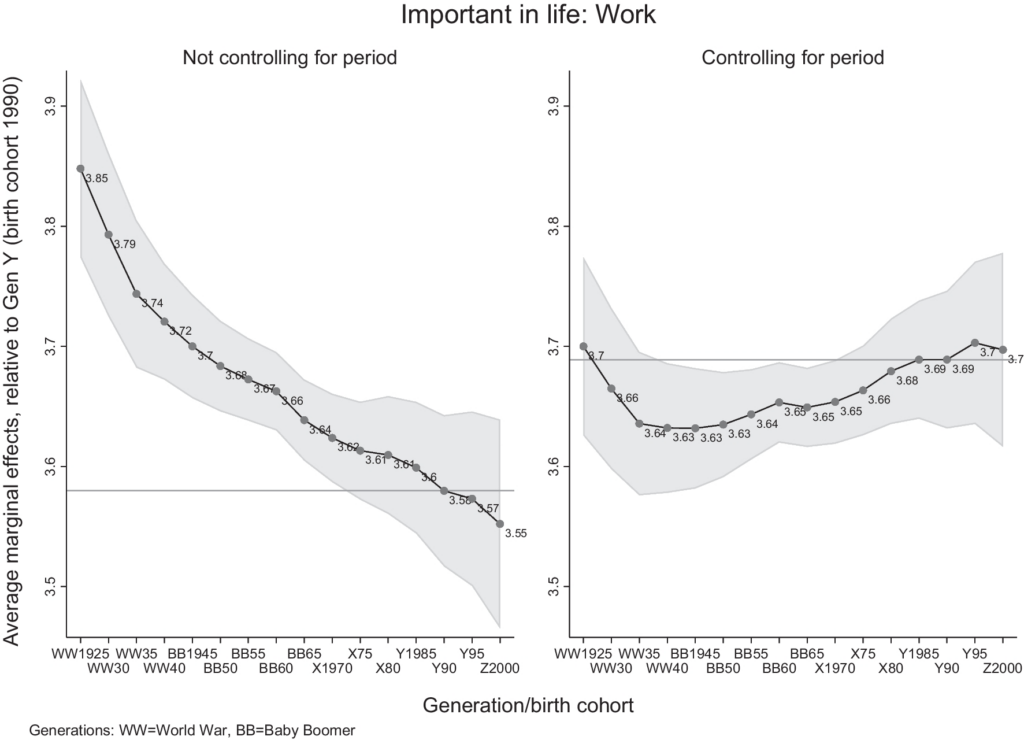

This is why I am writing this blog post. It is based on the article “Work Motivation Is Not Generational but Depends on Age and Period”, which I have just published in the Journal of Business and Psychology and which is available open access (for free and for everyone to access). Lo and behold, this peer reviewed article shows that if you take into account the effect of different life stages and different interview times, then there are hardly any generational effects that could explain work motivation or any other work-relevant trait. This means that, yes, young people think differently about work than old people. And yes, we all think differently about work than we used to. But no, some generations do not think systematically differently about work when asked at the same age and at the same time. If you do not take these age and period effects into account, then you get the left graph, where it seems as if one generation after another finds work less important.

But if you take period and age effects into account, then you get the right graph, where you can see that work motivation does not depend on when someone has been born. Time and again, this pattern emerges: it is not generational affiliation that explains our thinking, but when we are asked about something, because we now all think differently than we did in the past. So if you ask different generations at the same time, it turns out that they think almost exactly the same. I also checked this for the subjective importance of (1) leisure time, (2) good work hours, (3) the opportunity to use initiative, (4) generous holidays, (5) thinking that you can achieve something, (6) having a responsible job, (7) having a job that is interesting, (8) having a job that meets one’s abilities, (9) having pleasant people to work with, and (10) meeting pleasant people as important aspects of one’s job. Wherever you look, you find virtually no generational effects. I also searched in 34 different countries: Again, no generational effects to speak of.

So why do we continue to believe that generations exist when really they do not? I think that there are three reasons why we see generations where there are none:

Confusing generational effects with age and period effects

Our intuitive impression is often that, for example, “young people want to work less today”. This is not wrong. It just has nothing to do with generations, but is due to the fact that a) young people were always less eager to work than the middle-aged (which is called an age effect) and b) that all people (regardless of age and year of birth) consider gainful employment to be less important today than they did in the past (which is called a period effect). So we confuse age and period effects with generational effects and therefore see generations where what actually happens is that people change their attitudes with age and time periods.

However, to say that period effects rather than generation effects are responsible for something is not just a semantic difference. Rather, the difference has real consequences. For example, anyone who explains a lower work motivation through generational affiliation must assume that a certain generation and only this generation is less motivated to work. However, anyone who identifies a period effect as the reason behind changing work motivation can infer that the entire workforce is less motivated today than in the past. The former may need “generational coaching”, the latter requires an examination of the changing work motivation of all employees.

Generations as a new -ism

The second reason why we (want to) believe in generations is that “generationism” has become a new -ism, such as sexism or racism. Our brains love to divide people into groups, as this allows us to see our own social group as better others, which gives us a satisfying feeling. Yet, this is not only immoral, but often also illegal.

Fortunately, we have now understood that characteristics such as gender or skin color say little about people, because a) the groups that are kept apart by such criteria often do not differ in relevant characteristics and b) it is not okay either way to evaluate individuals based on their group characteristics, rather than perceiving them as individuals who may deviate from the group that we assign them to. Simply put, it does not do justice to an individual to categorize her as “woman”, “white” or “old”. However, the irresistible mechanism of 1) categorizing, 2) stereotyping and then 3) discriminating based on inborn characteristic happens not only with skin color or gender, but also with the characteristic of birth year. And so we end up with derisive statements such as “Ok Boomer” or “Generation Snowflake.”

However, discriminating individuals based on their birth year is just as unacceptable as racism or sexism. But while we rightly scandalize discrimination when it is based on gender or skin color, we do not (yet) scandalize discrimination when it happens on the basis of the innate characteristic of birth year. Yet discrimination based on one inborn characteric is no better than on another.

Generations as a business model

A third and last reason why we assume that generations exist, even though they do not, is that people simply make money with this claim. These self-proclaimed “youth researchers” or “Gen Z/Y understanders” must ignore scientific evidence that contradicts their business model, because their income depends on selling “generation-sensitive” coaching, books and key note speeches that advice on a phantom that is disguised as a phenomenon.

Just google it. You will discover an astonishing correlation: those who firmly claim that generations exist earn money with this claim, recommending themselves on their websites as generational experts to be be invited as coaches or speakers. Contrary to this, those who, on the other hand, demonstrate that it makes no sense to differentiate between generations do not profit financially from this claim but are usually boring university professors who do not make money by showing that generations do or do not exist. If you find an exception, send me an email. I am still searching.

So, this is it, empirically, generations do not exist across a wide range of attitudes. And those who try to make you believe otherwise probably do so because they profit from doing so.

If you have any questions about this, feel free to write to me on Twitter: https://twitter.com/Martin_Schroe

or Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/martinschroeder.bsky.social

And in the spirit of open science and replicability, you find the entire code with which I calculated my results with the open access article .